97 Things Every Programmer Should Know

- Act with Prudence

- Apply Functional Programming Principles

- Ask, “What Would the User Do?” (You Are Not the User)

- Automate Your Coding Standard

- Beauty Is in Simplicity

- Before You Refactor

-

Beware the Share

- The Boy Scout Rule

- Check Your Code First Before Looking to Blame Others

- Choose Your Tools with Care

- Code in the Language of the Domain

- Code is Design

- Code Layout Matters

-

Code Reviews

- Coding with Reason

- A Comment on Comments

- Comment Only What the Code Cannot Say

- Continuous Learning

- Convenience is Not an -ility

- Deploy Early and Often

-

Distinguish Business Exceptions from Technical

- Do Lots of Deliberate Practice

- Domain-Specific Languages

- Don’t Be Afraid to Break Things

- Don’t Be Cute with Your Test Data

- Don’t Ignore That Error!

- Don’t Just Learn the Language, Understand Its Culture

-

Don’t Nail Your Program into the Upright Position

- Don’t Rely on “Magic Happens Here”

- Don’t Repeat Yourself

- Don’t Touch That Code!

- Encapsulate Behavior, Not Just State

- Floating-Point Numbers Aren’t Real

- Fulfill Your Ambitions with Open Source

-

The Golden Rule of API Design

- The Guru Myth

- Hard Work Does Not Pay Off

- How to Use a Bug Tracker

- Improve Code by Removing It

- Install Me

- Interprocess Communication Affects Application Response Time

-

Keep the Build Clean

- Know How to Use Command-Line Tools

- Know Well More Than Two Programming Languages

- Know Your IDE

- Know Your Limits

- Know Your Next Commit

- Large, Interconnected Data Belongs to a Database

-

Learn Foreign Languages

- Learn to Estimate

- Learn to Say, “Hello, World”

- Let Your Project Speak for Itself

- The Linker is Not a Magical Program

- The Longevity of Interim Solutions

- Make Interfaces Easy to Use Correctly and Hard to Use Incorrectly

-

Make the Invisible More Visible

- Message Passing Leads to Better Scalability in Parallel Systems

- A Message to the Future

- Missing Opportunities for Polymorphism

- News of the Weird: Testers Are Your Friends

- One Binary

- Only the Code Tells the Truth

-

Own (and Refactor) the Build

- Pair Program and Feel the Flow

- Prefer Domain-Specific Types to Primitive Types

- Prevent Errors

- The Professional Programmer

- Put Everything Under Version Control

- Put the Mouse Down and Step Away from the Keyboard

-

Read Code

- Read the Humanities

- Reinvent the Wheel Often

- Resist the Temptation of the Singleton Pattern

- The Road to Performance is Littered with Dirty Code Bombs

- Simplicity comes from Reduction

- The Single Responsibility Principle

-

Start from Yes

- Step Back and Automate, Automate, Automate

- Take Advantage of Code Analysis Tools

- Test for Required Behavior, Not Incidental Behavior

- Test Precisely and Concretely

- Test While You Sleep (and over Weekends)

- Testing is the Engineering Rigor of Software Development

-

Thinking in States

- Two Heads are often Better Than One

- Two Wrongs Can Make a Right (and Are Difficult to Fix)

- Ubuntu Coding for Your Friends

- The Unix Tools Are Your Friends

- Use the Right Algorithm and Data Structure

- Verbose Logging will Disturb Your Sleep

-

WET Dilutes Performance Bottlenecks

- When Programmers and Testers Collaborate

- Write Code as if you had to Support it for the Rest of Your Life

- Write Small Functions Using Examples

- Write Tests for People

- You Gotta Care About the Code

- Your Customers Do Not Mean What They Say

Programming Wisdom #1 - Act with Prudence

“Pay off technical debt as soon as possible. It would be imprudent to do otherwise.”

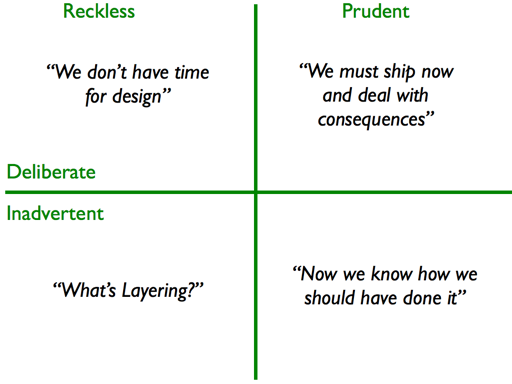

- Deliberate technical debt is when you choose ‘doing it quick’ over ‘doing it right’ with the understanding that you’ll come back and fix it later, but in the next iteration you become focused on new problems.

- Technical debt is a problem because you benefit from it in the short term, but you have to pay interest on it until it is fully paid off.

- This makes it harder to add features or refactor your code, making it a breeding ground for defects and brittle test cases.

- By the time you start fixing it, a whole stack of not-quite-right design choices may be layered on top of the original problem, making the code much harder to refactor and correct.

- However, there are times when you must incur technical debt to meet a deadline or implement a thin slice of a feature. In these situations,

- Track technical debt by writing a task card or logging it in your issue-tracking system and paying it back quickly.

- Track interest accrued on technical debt to make the cost visible. This will emphasize the effect on business value of the project’s technical debt and enables appropriate prioritization of the repayment.

Resources:

- https://martinfowler.com/bliki/TechnicalDebtQuadrant.html

- https://innolution.com/essential-scrum/table-of-contents/chapter-8-technical-debt

- https://innolution.com/blog/managing-the-accrual-of-technical-debt

Programming Wisdom #2 - Apply Functional Programming Principles

Of course, the functional programming approach is not optimal in all situations. For example, in object-oriented systems, this style often yields better results with domain model development than with user-interface development. Master the functional programming paradigm so that you are able to judiciously apply the lessons learned to other domains.

- Mutable variables are a leading cause of defects in Object-Oriented Code.

- Visibility semantics (eg. Public, Private, Protected keywords in Java) help reduce these defects or at least drastically narrow down the location of mutable variables.

- However, the true culprit may be designs that employ excessive mutability (typically taught in Object-Oriented Programming courses).

- Having a design with a high degree of referential transparency helps eliminate this unnecessary mutability.

- Referential transparency implies that functions consistently yield the same results given the same input, irrespective of where and when they are invoked. i.e. Function evaluation depends less (ideally, not at all) on the side effects of mutable state.

- Referential transparency can be achieved by having an astute test-driven design and by being sure to “Mock Roles, not Objects”, resulting in a design that typically has

- Better responsibility allocation with more numerous, smaller functions that act on arguments passed into them, rather than referencing mutable member variables.

- This makes it easier to locate where a rogue value is introduced, leading to fewer defects and simple-to-debug code.

- Nothing will get these ideas as deeply into your bones as learning a functional programming language, where this model of computation is the norm.

Resources:

- Mock Roles, not Objects

- Professor Frisby’s Mostly Adequate Guide to Functional Programming

- What is “Semantics visibility”?

- What is a side-effect of a function in Python?

Programming Wisdom #3 - Ask, “What Would the User Do?” (You Are Not the User)

False consensus bias is when we assume that other people think like us. It explains why programmers have such a hard time putting themselves in the users’ position.

- Users don’t think like programmers. They don’t recognize the patterns and cues programmers use to work with, through, and around an interface.

- The best way to find out how a user thinks is to watch one complete a real task using our product.

- Avoid tasks that are too specific.

- Get the user to talk through their progress. Don’t interrupt. Don’t try to help.

- Keep asking yourself “Why are they doing that?” and “Why are they not doing that?”

- Users do a core of things similarly. They try to complete tasks in the same order - and they make the same mistakes in the same places.

- Design around this core behavior.

- Tool tips are more useful than help menus because when users get stuck, unlike programmers, they narrow their focus.

- When they narrow their focus, it becomes harder for them to see solutions elsewhere on the screen.

- If you still need to have instructions or help text, make sure to locate it right next to your problem areas.

- Provide one really obvious way of doing things than two or three shortcuts.

Programming Wisdom #4 - Automate Your Coding Standard

But if it’s such a problem, why is it that we want a coding standard in the first place? Well-formatted code doesn’t earn you points with a customer that wants more functionality.

- Following a coding standard that everyone on the project agrees on ensures that

- Nobody can “own” a piece of code just by formatting it in his or her private way.

- Developers are prevented from using certain antipatterns to avoid common bugs.

- Development speed is maintained from the beginning to the end.

- Following a coding standard can be quite a boring task if it isn’t automated and enforced where possible. So,

- Make code formatting part of the build process.

- Use static code analysis tools to scan for unwanted antipatterns. If found, break the build.

- Automatically check the results of test coverage. Break the build if test coverage is low.

- For things that can’t be automated, consider them a set of guidelines supplementary to the coding standard that is automated, but accept that you and your colleagues may not follow them as diligently.

- Have a dynamic coding standard that evolves as the project evolves.

Programming Wisdom #5 - Beauty is in Simplicity

“Beauty of style and harmony and grace and good rhythm depends on simplicity.” - Plato

- No matter how complex the total application or system is, keep the individual parts simple

- Simple objects with a single responsibility containing simple, focused methods with descriptive names

- Simple relationships with the other parts of the system

- Simplicity in code enables

- Readability

- Maintainability

- Speed of development

- Beauty

Resources:

Programming Wisdom #6 - Before You Refactor

- Start by taking stock of the existing codebase and the tests written against that code.

- This helps you understand the strength and weaknesses of the code as it currently stands.

- Avoid the temptation to rewrite everything.

- Throwing away the old code, especially if it was in production, means that you are throwing away months (or years) of tested, battle-hardened code that may have had certain workarounds and bug fixes you aren’t aware of.

- If you don’t take this into account, the new code you write may end up showing the same mysterious bugs that were fixed in the old code. This will waste a lot of time, effort, and knowledge gained over the years.

- Many incremental changes are better than one massive change.

- Incremental changes allow you to gauge the impact on the system more easily through feedback, such as from tests.

- After each development iteration, it is important to ensure that the existing tests pass.

- Add new tests if the existing tests are not sufficient to cover the changes you made, but don’t throw away tests from old code without due consideration.

- Personal preferences with respect to the style and structure of code and ego shouldn’t get in the way.

- New technology is an insufficient reason to refactor.

- Unless a cost-benefit analysis shows that a new language or framework will result in significant improvements in functionality, maintainability, or productivity, it is best to leave it as it is.

- Remember that humans make mistakes.

- Restructuring will not always guarantee that the new code will be better—or even as good as—the previous attempt.

Resources:

- https://amberwilson.co.uk/blog/how-to-approach-a-new-codebase/

- https://blog.jamesmichaelhickey.com/refactoring-legacy-monoliths-part-2-convincing-management/

- https://wiki.c2.com/?EconomicsOfRefactoring

Programming Widsom #7 - Beware the Share

As I worked through my first feature, I took extra care to put in place everything I had learned—commenting, logging, pulling out shared code into libraries where possible, the works. The code review that I had felt so ready for came as a rude awakening—reuse was frowned upon!

- Shared code can create dependencies between business domains. Increased coupling

- Will require both the business domains to synchronize before making any changes.

- Increases the maintenance cost as well as testing requirements of the code.

- We can avoid these problems by being mindful of the business context in which the reused code was originally being used. Only reuse code that has localized dependencies.

- This means each piece of code can evolve independently.

- Each code can change its logic to suit the needs of the system’s changing business environment.

Resources:

- https://www.innoq.com/en/blog/code-reuse-or-redundancy/

Programming Wisdom #8 - The Boy Scout Rule

“Try and leave this world a little better than you found it.” - Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell

- Follow the boy scout rule in your code. You don’t have to make every module perfect before you check it in. You simply have to make it a little bit better than when you checked it out.

- Add clean code to a module.

- Clean up at least one other thing before you check the module back in.

- Teams help one another and clean up after one another. They do this because it’s good for everyone, not just good for themselves.

- This could see help end the relentless deterioration of our software systems. Instead, our systems would gradually get better as they evolve.

- Teams would care for the system as a whole, rather than just individuals caring for their own small part.

Programming Widsom #9 - Check Your Code First Before Looking to Blame Others

“Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth.” - Sherlock Holmes

- Check your code instead thoroughly using these techniques before blaming the compiler:

- Isolate the problem, stub out calls and surround it with tests.

- Check calling conventions, shared libraries and version numbers.

- Explain it to someone else.

- Look out for stack corruption (especially if adding trace code makes the problem move around) and variable type mismatches.

- Try the code on different machines and different build configurations, such as debug and release.

- Question your own assumptions and the assumptions of others.

- When someone else is reporting a problem you cannot duplicate, go and see what they are doing. They may be doing something you never thought of or are doing something in a different order.

- Favor simple code design for multithreaded code because debugging and unit tests can’t be relied on to consistently catch bugs in multithreaded code.

Programming Widsom #10 - Choose Your Tools With Care

Start small by using only the tools that are absolutely necessary.

Modern applications are very rarely built from scratch . They are assembled using existing tools—components, libraries, and frameworks— for a number of good reasons:

- Applications grow in size, complexity, and sophistication, while the time available to develop them grows shorter. It makes better use of developers’ time and intelligence if they can concentrate on writing more business-domain code and less infrastructure code.

- Widely used components and frameworks are likely to have fewer bugs than the ones developed in-house.

- There is a lot of high-quality software available on the Web for free, which means lower development costs and greater likelihood of finding developers with the necessary interest and expertise.

- Software production and maintenance is human-intensive work, so buying may be cheaper than building.

However, choosing the right mix of tools for your application can be a tricky business requiring some thought. In fact, when making a choice, you should keep in mind a few things:

- Different tools may rely on different assumptions about their context—e.g., surrounding infrastructure, control model, data model, communication protocols, etc.—which can lead to an architectural mismatch between the application and the tools. Such a mismatch leads to hacks and workarounds that will make the code more complex than necessary.

- Different tools have different lifecycles, and upgrading one of them may become an extremely difficult and time-consuming task since the new functionality, design changes, or even bug fixes may cause incompatibilities with the other tools. The greater the number of tools, the worse the problem can become.

- Some tools require quite a bit of configuration, often by means of one or more XML files, which can grow out of control very quickly. The application may end up looking as if it was all written in XML plus a few odd lines of code in some programming language. The configurational complexity will make the application difficult to maintain and to extend.

- Vendor lock-in occurs when code that depends heavily on specific vendor products ends up being constrained by them on several counts: maintainability, performances, ability to evolve, price, etc.

- If you plan to use free software, you may discover that it’s not so free after all. You may need to buy commercial support, which is not necessarily going to be cheap.

- Licensing terms matter, even for free software. For example, in some companies, it is not acceptable to use software licensed under the GNU license terms because of its viral nature—i.e., software developed with it must be distributed along with its source code.